Can bacteria build cities?

Bacteria can actually build structures that can be compared to our cities. This form of life is known as biofilm.

If you don't brush your teeth for a long time, a small "city" can develop in your mouth during this time. Especially if you like to eat sugary foods, microbes like to erect their "buildings". The walls of the microbial city consist of metabolic products that the bacteria excrete after eating. Together with the saliva and bacterial cells, a coating (plaque) forms. This can contain millions to billions of microorganisms.

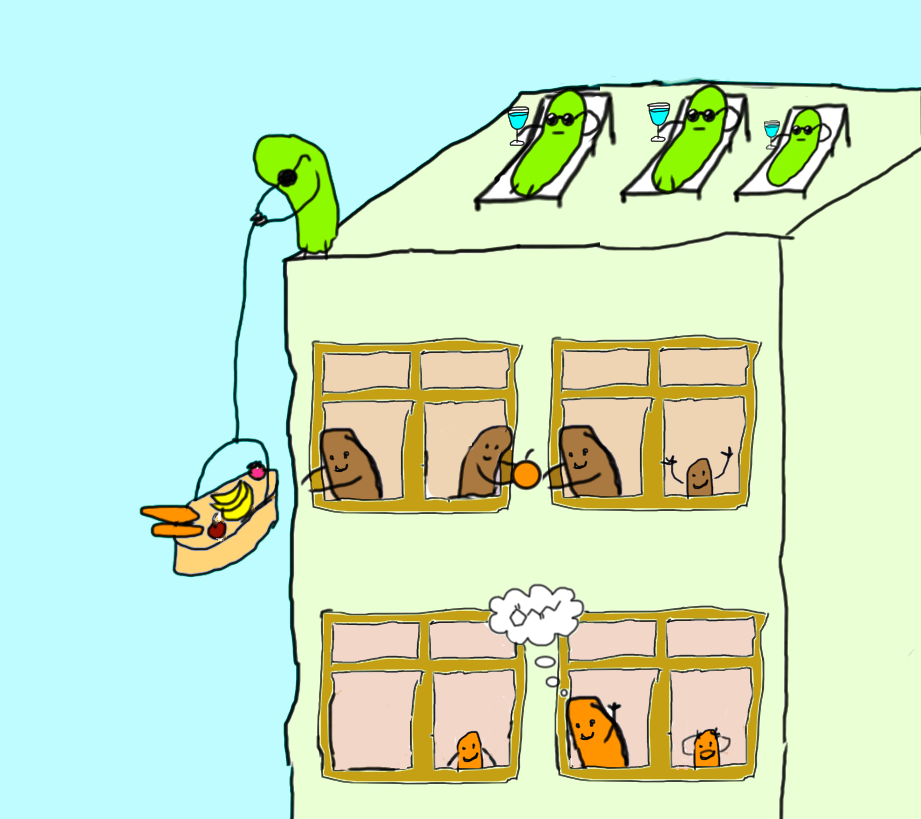

During biofilm formation, the bacteria attach themselves to a surface and excrete mainly polysaccharides, but also proteins and lipids, which are summarised as extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). The EPS form a three-dimensional network, the supporting matrix. The EPS also serve as a nutrient source and communication network and provide mechanical stability. After an initial expansion in width, several layers or storeys develop - similar to a city.

In many parts of our body, such as the intestines, vagina, ears and nose, microbes can colonise as a biofilm without being harmful to us. For example, probiotic bacteria help us to digest food and also prevent other harmful bacteria from gaining a foothold. In the case of cystic fibrosis, however, pathogens (in this case mostly Pseudomonas aeruginosa) can become established, form biofilms in the lungs and thus trigger a chronic disease.

Biofilms can also form on stones, metal surfaces, in pipes, toilets, lakes, rivers, in the sea or on glaciers. You know the slimy film from the coffee cup that hasn't been rinsed for a long time. Natural biofilms can contain many different microorganisms. Such "microbial mats" consist of several, often differently coloured layers with special functions. The waste products of one layer can, for example, serve as a source of nutrients for another layer. For example, cyanobacteria can use photosynthesis to produce oxygen and sugar in an upper layer, which heterotrophic organisms in lower layers of the microbial mats can utilise.

As the biofilm matrix is very difficult to analyse, it is regarded as the "dark matter of biology". In recent years, scientists have been trying to use biofilms to our advantage. In sewage treatment plants, biofilms support wastewater treatment. The metabolic properties of the bacteria living in the biofilm can help as "catalytic biofilms" to produce high-quality chemicals, in the case of cyanobacteria even with the help of solar energy.

Read more:

© Text and figure: Mahir Bozan und Sonja Höhmann / VAAM, mahir.bozan[at]ufz.de, Use according to CC 4.0